Annie Nathan Meyer

February 19, 1867-September 23, 1951

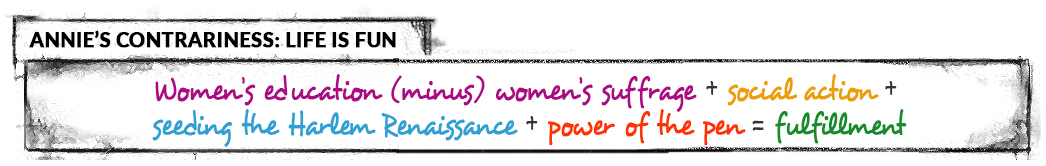

The life of the founder of Barnard College is a study in contradictions.

I, Charley Morton, time traveler and science geek, have set out to record my interview with this trailblazing advocate of women’s education and Broadway-produced playwright as part of my “Superheroes of History” project. Finding some unlikely letters between her and Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston, I just had to investigate!

"Had my ambition been less, the gap between idea and fulfillment would perhaps have been slighter.”

Charley Morton: What was life like for you growing up?

Annie Nathan Meyer:

My family first came to America from Holland in the mid-1600s to what was then called New Amsterdam, now New York City. As Sephardic Jews, we left the old country due to religious persecution. Anti-Semitism is an old story.

But the family flourished in the New World. They established the first Sephardic Jewish congregation in the city, Shearith Israel. It exists to this day. My great-grandfather, Gershom Mendes Seixas, the congregation’s first clerical leader, became known during the American Revolution as the “patriot rabbi” for refusing to pray for the British King George III.

The descendants of those original families went on to become among America’s most prominent captains of industry, banking, law, arts and government. My cousin Emma Lazarus wrote the poem that is inscribed on the Statue of Liberty, “Give me your tired, your poor...” You know the one. My cousin Benjamin Cardozo was a United States Supreme Court Justice.

I have always said, we Sephardic families are the closest thing that exists to “American royalty.”

For my brothers and sisters and me, growing up, this glory meant nothing. My father was a stockbroker. He lost all our money in the Great Stock Market Crash of 1875, moved our family to Green Bay, Wisconsin, and tried, unsuccessfully, to make a living at the railroads. When that failed, he left us. My mother, a genteel Southern lady who had always suffered from a nervous temperament, was broken by the loss.

Charley Morton: Tell me about your work—especially how you see science, technology, culture and art combining to create new/different insights.

Annie Nathan Meyer:

I have been more interested in cultural pursuits, among them education, women’s rightful roles in society, and the conflicting claims of career and marriage on professional women. As a cultural critic, I have written about a wide variety of topics, among them nature’s ability to uplift and restore, art and literary criticism. I have also long advocated for racial equality, and supported those people and organizations that might advance this cause.

But it is not only writing, philanthropic and social causes that captivate me—my husband, Dr. Alfred Meyer, and I play piano duets for nearly 60 years. I glory in nature, and wrote My Park Book, to celebrate Central Park. I felt obliged to ride skillfully, for a woman to have been seen wobbling helplessly about, or trying to run up a score of broken lamp-posts, would scarcely have conduced to popularize the sport for her sex.

As a Nature-lover who has always sat at my feet — the wheel is merely a delightful means of getting there . . . . I derive great satisfaction from the spice and freedom doing something in the face of society’s frown. I even invented a perfectly satisfactory wheeling costume, made over from a discarded skirt.

Charley Morton: Wow, I guess you might say that women riding bikes was the “bees knees” in the language of the day a century ago. In fact, my friend Sabrina tells the history of bikes, sports, fashion and women’s higher education in a story at the Edge of Yesterday. Seems to check almost all the boxes of stuff you supported back in the day!

Annie Nathan Meyer: Yes. Well, I do take issue with her assertion about how women riding bikes advanced the cause of women’s suffrage. I think there is a grave danger to the moral force of womanhood in woman’s increasing participation in organized effort, in public life.

Charley Morton:

Ahem, well. . .not sure that whole “moral force of womanhood” argument has been the biggest concern with women’s having gotten the vote, at least not in my century.

But let’s get back to the interview. Were there courses you took, or any special line of study?

Annie Nathan Meyer:

As far back as I can remember, I was filled with a passionate desire to go to college. My father did not want me to attend college at all—he said that men hated intelligent woman.

God, I’d like to be recognized! In 1885, I could only attend the Collegiate Course for Women at Columbia University. Women were not permitted to attend laboratories or lectures. When it came time to take my examinations, the Professor had … told me to read certain pages and I had done so; but he calmly proceeded to base his questions, not on the textbooks assigned, but entirely upon the lectures which he had given to his classes – lectures which I, of course, had not been permitted to attend.

Charley Morton: Oh, kind of like a correspondence course? I think those were a thing for a while.

Annie Nathan Meyer:

We may acknowledge that the day is past when it is necessary seriously to plead the capacity of women to accomplish certain things; that victory has been won with tears of blood; but the fight still centers about the propriety of it.

In 1887, I did not meet with any professor who was not in favor of establishing an annex for women with its instruction furnished by the professors and other instructors of Columbia College (now University). A graduate of the Columbia Annex would readily receive the degree of B.A.

Charley Morton: It’s so much easier today. Students can take classes on line from anywhere, any time. On campus, they even go to class in their pjs!

Annie Nathan Meyer: (She looks shocked at this idea.)

Charley Morton: Moving on. You established Barnard College in New York City. That is amazing! So let’s talk about your friendship with Zora Neale Hurston, and support for her education and career. I know you got her a scholarship to attend Barnard as the college’s first black student. Was that something you got pushback for?

Annie Nathan Meyer:

I first met Zora in 1925 at an awards dinner in New York, where she was feted for winning a writing contest for Opportunity magazine, sponsored by the Urban League. I was immediately impressed with her talent and charm.

What’s more, I had been working on a script for a play, Black Souls, about a white Southern woman who was attracted to a Black man. I felt utterly unworthy to accomplish such a great theme, and never approached a theme with such humility.

Charley Morton: Wow! We’re talking the Jim Crow South, here. That must have been a pretty daring story at the time! And you wanted to put it on a New York stage?

Annie Nathan Meyer: I was always more of a pioneer than people realize.

Charley Morton: So then what happened? Did you ask Zora for writing advice?

Annie Nathan Meyer: Oh my, yes! We corresponded about the script. She read drafts and wrote that Black Souls was “immensely moving. . .accurate. . .brave, very brave without bathos.”

Charley Morton:

Bathos. What a great word! I need to remember that. Esme says it means, “An abrupt descent from lofty or sublime to the commonplace; anticlimax.” I’m going to have to use that in my college application essay.

So, like, in this case, she must have meant keeping it real, right?

Annie Nathan Meyer: Real. . .. (Glancing over at Charley’s notes). Esme? Who is. . .? Where is. . .?

Charley Morton: Oh, Esme’s my AI. (Annie looks puzzled). You know, a chat bot? Or, like when a secretary would take dictation from her boss, but she’s a robot?

Annie Nathan Meyer: A robot is taking dictation and talking to you?

Charley Morton: Um, well, yeah. . .oh, no, never mind! I just have a couple more questions before we wrap up. What’s your dream? I am interested in any stories you might like to share about your experiences in following your dream.

Annie Nathan Meyer: As a girl, I grew up heart-hungry, brain-famished. Although I have been ahead of my time, my life has been extremely worthwhile and, above all, it has been fun.

Charley Morton: Yes, fun. That’s a good reminder. So, for teens like me who want to do it all, do you have any advice?

Annie Nathan Meyer: Be someone who stands and dares. Listen honestly. Get Out!

Want to Learn More?

- “Annie Meyer.” Prabook.com

- Brock, H. I. “Her College Was Barnard; It's Been Fun. an Autobiography. by Annie Nathan Meyer. 302 Pp. New York: Henry Schuman. $3.50.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 9 Mar. 1952

- Goldenberg, Myrna. “Annie Nathan Meyer.” Jewish Women's Archive

- Goldenberg, Myrna. “Annie Nathan Meyer.” Jewish Women's Archive

- Meyer, Annie Nathan. Barnard Beginnings. Houghton Mifflin, 1935.

- Meyer, Annie Nathan. It's Been Fun: An Autobiography. H. Schuman, 1951.

- “A Spicy Spin through the Park?” Golden Gate Park: Views from the Thicket, 25 Feb. 2011.