Great Migration: Starting Over

The Great Migration in the early 20th century north meant Black Americans moving from a predominantly rural and small-town South to the great cities of the North. Starting over was a big adjustment for everyone, for better and, sometimes, worse.

Life in the South and life in the North have always been strikingly different from one another. Whether it be the weather, the food, the accents, or the popular sports, the two regions of the country have always had their own distinct culture.

However, attitudes towards race in these respective regions have had more in common than one may think-- particularly during the time of the Great Migration. Racism was prevalent throughout the United States and migrating to the North did not mean that being a Black American became easier. Not only did they continue to face racism, they also had to adapt to living in the bustling, overcrowded cities that were a completely different world compared to the farms and plantations they had always known.

Although there were more economic opportunities for Blacks in the North, they didn’t come without a price. By 1919, one million African Americans had left the South, and cities were becoming increasingly more crowded. In just three years, the Black population in New York City rose by 66 percent, in Chicago by 148 percent, in Philadelphia by 500 percent, and in Detroit by 611 percent.

By contrast, before the Great Migration began, the relatively sparse number of African Americans residing in the North had lived in small clusters in different neighborhoods throughout the cities. However, as opposition to the increasing number of African Americans continued to intensify, White bankers and realtors began to close the real estate market off from them, resulting in the establishment of ghettos. There was nowhere near enough adequate space available for the hundreds and sometimes thousands of Black families streaming into the cities; as competition for housing intensified, rents rose as well.

The living conditions in these ghettos were horrific--cramped, rancid, and filthy quarters. The spaces were often poorly ventilated, and this factor, plus insufficient rest and lack of proper nutrition, greatly contributed to the horrifyingly high death rates within Black communities. More than a quarter of Black babies died before their first birthday--a mortality rate twice that of Whites.

Racism remained a constant issue that continued to go unresolved. Migrators faced a resurgence of Ku Klux Klan activity, and racial tensions worsened as White Northerners began to feel that their opportunities for work were now threatened by the vast numbers of African Americans arriving in the cities. Many African Americans were scapegoats to White Northerners, who blamed them for low wages, poor factory conditions, and white unemployment.

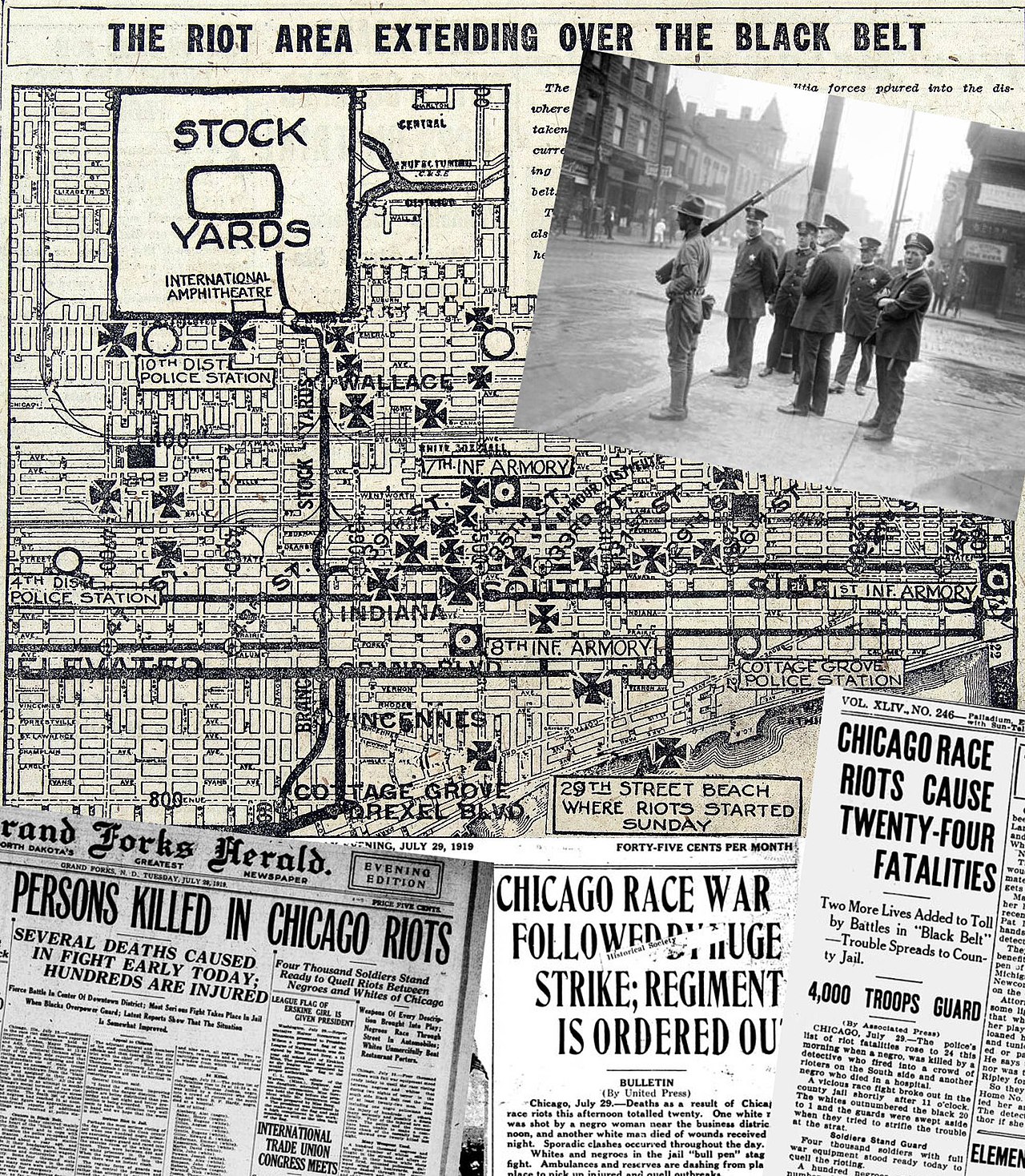

A white gang looking for African Americans during the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. This and a subsequent picture at The Crisis Magazine 1919, Vol 18 No.6

Members of labor unions also greatly resented the tens of thousands of black migrants coming to the cities. There was now a surplus in labor, and many large businesses were more than willing to employ Black workers. In 1929, for example, there were nearly 25,000 black automotive workers in the United States-- and nearly half of them worked in Henry Ford’s assembly lines. The surplus in workers meant that labor unions became essentially powerless as the need for workers drastically decreased, and the majority of White union members refused to invite Black workers to join them.

Map of 1919 Chicago Race Riot Hot Spots extending over the Black Belt. Five police officers and a National Guard soldier with a rifle and bayonet standing on a corner in the Douglas neighborhood

Tensions between Black migrants and White Northerners quickly escalated from resentment to violence. The summer of 1919 was particularly destructive, as urban citizens experienced several devastating riots-- one of the most famous being the Chicago Race Riot, which claimed the lives of 23 Black and 15 White Americans.

From Hattiesburg to Harlem: Celebrating the Past and Inspiring the Present

Inside the Northern ghettos, many of these new city dwellers found that they had experienced similar obstacles and experiences. Sharing their stories brought these communities of poor and oppressed people closer together, and soon a new urban African American culture was developing within these neighborhoods. Rather than despair, people living in these communities fostered hope-- particularly in Harlem in New York City, well- known for spurring a cultural renaissance during this time. The developing sense of Black community and pride in Harlem soon became a driving theme in the artistic movement that came to be known as the Harlem Renaissance: the rebirth of African American culture as Black writers, actors, and musicians used their talents to glorify and celebrate their traditions. Soon, throughout cities in the North, many ghettos similar to Harlem became symbols of vibrance and culture, rather than of poverty and squalor.

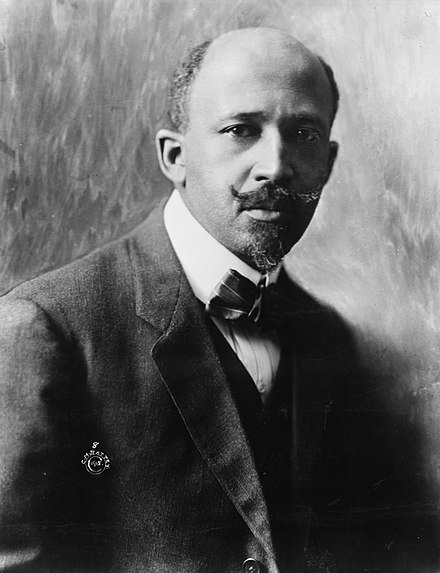

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois

Black leaders such as sociologists W.E.B. Du Bois and Charles Spurgeon Johnson worked tirelessly to bring recognition to the up-and-coming poets and novelists living in Harlem. Johnson was able to help establish connections between talented black writers such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, who soon found that their work was being published in mainstream publications, attracting the attention of many prominent White members of New York society who began to develop an interest in Harlem’s literary scene.

The curiosity of these White patrons eventually sparked to the point that many began coming to Harlem to experience its vibrant nightlife firsthand. The exceptional music scene encouraged them to return, and influential jazz musicians such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington performed frequently, bringing white and black New Yorkers together to experience the increasing pride and celebration of the new urban African American culture.

The Harlem Renaissance, unfortunately, was short-lived, peaking in the 1920s and ending in the 1930s when the country was hit by the Great Depression. But throughout its duration, it remained a symbol for the Great Migration and had lasting impacts on American society.

Seeing a Second Wave

The end of the Harlem Renaissance by no means signaled the end of the Great Migration. A second wave of migrants, known as the “Second Great Migration” came to the North in the 1940s when WWII brought on many new job opportunities. Even after the war ended, large numbers of migrants continued to come to the North until 1980.

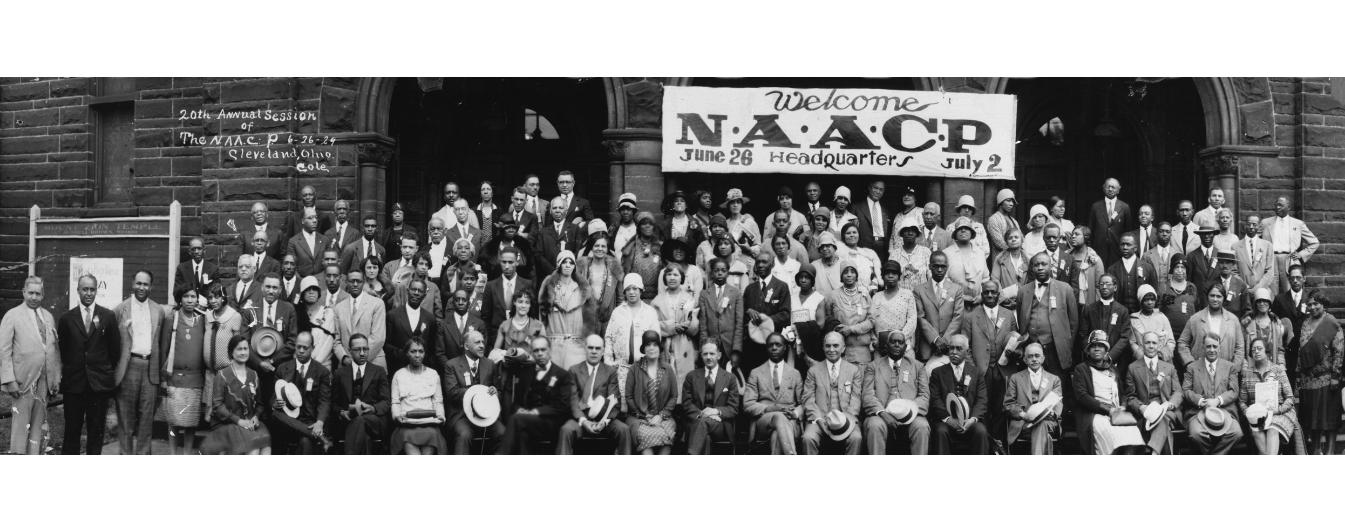

The Great Migration gave urban Black communities more power than they had ever experienced. By virtue of living together in the cities, it became easier to create and work for activist organizations, many of which were dedicated to the cause of civil rights for African Americans. Others worked to improve the poor social and economic conditions African Americans faced. Two prominent organizations during this time were the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the National Urban League.

The 1929 annual meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), courtesy of the Library of Congress

It was also much easier for Black Americans to vote in the North than in the South. Although the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870, giving Black Americans the right to vote, several Southern states placed restrictions on this right. Some of these restrictions included literacy tests, constitutional quizzes, or a poll tax that would have to be paid prior to voting. As lawmakers had intended, these restrictions prevented many Blacks living in the South from being able to vote. There were not nearly as many restrictions in the North as there were in the South, and this made it easier for black Americans living in the North to engage themselves in American politics. This as well as a fostering sense of pride within the African American community set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement.

History paves the way to the present

In our society today, we are experiencing another significant event in American history: the Black Lives Matter movement. Sparked by a populist wave, the Black Lives Matter movement is being facilitated primarily by everyday people, similar to how it was everyday Black Southerners who participated in the Great Migration.

Black Lives Matter Plaza Sign Indicating the Plaza. Washington DC, 2020

While the Great Migration was fueled by a hope for opportunities and liberation, the Black Lives Matter movement has worked to remind people of that hope. The hope Black migrants fostered decades ago has been rediscovered by many of those involved in the Black Lives Matter movement, as participants begin to organize and advocate for righting long-held injustices and come together, across racial boundaries, to fight for respect, freedom, and equality.

Want to Learn More?

“Articles.” The Harlem Renaissance: What Was It, and Why Does It Matter? | Humanities Texas, https://www.humanitiestexas.org/news/articles/harlem-renaissance-what-was-it-and-why-does-it-matter

Christensen, Stephanie. “The Great Migration (1915-1960).” Welcome to Blackpast •, 22 Aug. 2019, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/great-migration-1915-1960/

“The Great Migration.” AAME, http://www.inmotionaame.org/migrations/landing.cfm;jsessionid=f830975971616468119398?migration=8&bhcp=1

“Great Migration: The African-American Exodus North.” NPR, NPR, 13 Sept. 2010, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=129827444.

“The Harlem Renaissance.” Ushistory.org, Independence Hall Association, https://www.ushistory.org/us/46e.asp

History.com Editors. “Harlem Renaissance.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 29 Oct. 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/harlem-renaissance.

History.com Editors. “Jim Crow Laws.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 28 Feb. 2018, https://www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/jim-crow-laws

History.com Editors. “The Great Migration.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 4 Mar. 2010, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/great-migration

“Image.” AAME, www.inmotionaame.org/migrations/topic.cfm?migration=8.

“Moving North, Heading West : African : Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History : Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress : Library of Congress.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/african7.html.

“Sharecropping.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/themes/sharecropping/

Wilkerson, Isabel. “The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Great Migration.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Sept. 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/long-lasting-legacy-great-migration-180960118/

Women at the Center. “Teaching Women's History: Women of the Great Migration.” Women at the Center, 27 June 2018, https://womenatthecenter.nyhistory.org/women-of-the-great-migration/